Two faces, Two dials, Two identities

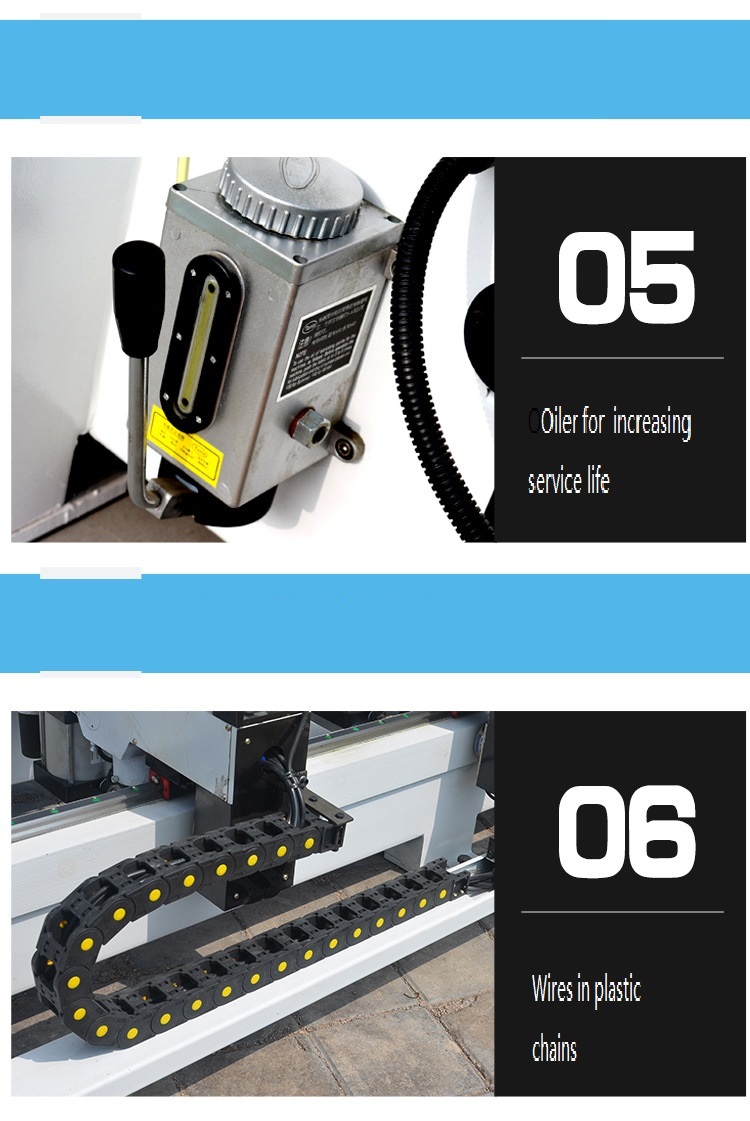

High performance escapement with “triple pare-chute” protection Single Phase Edgebander

Quality, craftsmanship, and reliability; these are the three things that everyone wants when shopping for a new car.

It is also what car commercials whisper as artistic shots of the car driving down an empty and slightly wet road are shown.

When someone buys a very expensive machine that will hopefully be around for a significant portion of one’s life, car marketers understand the benchmarks that should be considered first.

So why is it that when another very expensive machine, a wristwatch, is advertised, does the marketing sometimes revolve around heritage, passion, rarity, and other things not really related to the inherent quality of the watch?

Not all advertising is the same, of course, and some of it does communicate at length about the craftsmanship that goes into such pieces. But very often the details about exactly what does make one watch better than others is woefully underrepresented.

This is where certifications and seals come in.

Over the history of watchmaking, governing bodies have sought to codify what makes a watch worthy of being considered “the best.”

Between C.O.S.C. (Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres) and ISO (International Organization for Standardization) standards, the Poinçon de Genève (Geneva Seal) and the Fleurier Quality Foundation certification, to the new METAS Master Chronometer certification and the various brand-specific seals and certifications, there are clearly many ways to prove a watch is magnificent.

But unless you have read the literature or are very well versed in the technical aspects of watchmaking and manufacturing, you are unlikely to know what they all all mean.

So today I, your resident nerdwriter, will take one of the oldest and most widely known certifications, the Geneva Seal, and dissect it so we can have a complete look into what constitutes a watch worthy of it and why it matters.

The Geneva Seal is very old, having been proposed on November 6, 1886 by the Grand Council of the Republic and Canton of Geneva as a way to certify a level of quality for which the canton was becoming known.

Geneva Seal (Poinçon de Genève)

The purpose was twofold: to ensure that the Geneva name and trademark proved the origin and quality of the watch and to encourage talented watchmakers to stay in Geneva instead of taking their talents abroad (as was beginning to happen).

In the last few years, the requirements for the Geneva Seal have been adjusted and updated, with a major overhaul in 2011 and another adjustment in 2014. These additions have taken the seal into the twenty-first century to create a level of certification and exclusivity worthy of notice.

While the Geneva Seal has found competition from other strict certifications, it is the only certification that is indicative of and limited to the canton of Geneva, the famed epicenter of Swiss watchmaking.

The process for obtaining permission to use the Geneva Seal is rather straightforward but also very labor intensive, though not every watch bearing the seal is required to be inspected by the office of the Poinçon de Genève after the initial certification. Most of that is carried out by each respective brand’s personnel in a dedicated office of the manufacture.

The process begins with an application to the Foundation Council of the Geneva Laboratory of Horology and Microengineering to be considered as a candidate for use of the seal.

This organization is now under the umbrella of Timelab, where the inspection, certification, and marking of the seal take place. To even be considered for application there are base requirements to meet: only mechanical movements and modules crafted to the highest standards are considered while the assembly, adjustment, and casing up must take place within the borders of the Canton of Geneva by a company registered with the Trade Register of the Canton of Geneva.

You may notice that these requirements already allow for any and every component to be physically fabricated and finished outside of Geneva, and when reading the language, possibly fabricated anywhere in the world.

There is no requirement for the actual construction of components to be limited geographically, only the final assembly and adjustment. This allows a brand to hold an office and assembly workshop inside the canton while the rest of the manufacture is actually offsite.

Since manufacturing facilities tend to require larger spaces, this is a very cost-effective way to be based and registered in Geneva without needing to own extremely expensive square footage.

The Traditionnelle Minute Repeater Tourbillon is certified by the Geneva Seal, as are all Vacheron Constantin timepieces

If a brand meets the base requirements it can submit a movement (and corresponding watch) for assessment and approval. It must provide a complete set of technical 2D drawings, all of the individual components and/or modules, an assembled movement, and all external components (case rings, pushers, screws, and other case components) to be judged for adherence to the outlined requirements.

Once a movement is approved, the brand creates a “reference kit” of all the components plus an assembled movement (essentially two movements) that become property of Timelab and can be used as reference for future audits and in the case of a dispute.

Timelab then drafts an approval report to be given to the brand outlining the details of the approval. The process usually requires around two weeks to complete.

From there, it is chiefly up to the brand to certify each movement at various points throughout the assembly process. Which means that each component and the overall requirements are compared to the standard to ensure that the pieces are identically finished and the watches perform as similarly as possible. This is overseen by Timelab with periodic inspections.

It is here that a dispute may arise; the reference kit is used to provide a baseline for comparison and stands as the authoritative proof of quality.

But none of this actually tells us what the requirements are, how they are applied, and what it means for a watch to bear the Geneva Seal, so let’s break down all of the requirements and what it means for the movement and watch as a whole.

The Geneva Seal is visible on the left of the movement of this Vacheron Constantin Traditionnelle Minute Repeater Tourbillon

The requirements to qualify as worthy of the Geneva Seal

The requirements mainly have to do with how each component is finished and to what level each finish must be taken. Over the years there have been rewordings and adjustments or additions made to coincide with the technology and processes used in the industry.

The largest update occurred in 2011 when a significant amount of new language was added, as well as the entire idea of testing the movement while in a watch case, testing the case itself, and verifying performance criteria suitable for a chronometer.

Obviously those ideas were nothing new in the industry, but the inclusion resulted in the Geneva Seal becoming reinvigorated and worthy of pride as a defining certification that only the best of the best could achieve.

As we walk through the latest requirements for the Geneva Seal, I will point out where it might differ from the past requirements for an important reason. I have put the actual wording of the requirements italics and follow that up with my assessment of what it means for the components.

According to regulations, all visual inspection of components is carried out under 4x magnification. If something is unclear then up to 15x magnification can be used for verification.

The first Geneva Seal-certified Ateliers de Monaco wristwatch

It begins with base plates, bridges, and plates for additional mechanisms. Since these components are some of the largest visual pieces in a movement, every surface is required to be finished in some manner and all machining marks removed. These components must have:

Theoretically this could mean straight graining, bead blasting or applying a satin finish, polishing, black polishing, guilloche, or a variety of other creative ways to finish a surface that looks particularly nice, consistent, and removes all traces of manufacturing.

A Geneva Seal-certified Ateliers de Monaco movement

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

Roger Dubuis is a good example of a brand that pushes the boundaries of design and finishing yet fully complies on a majority of its models to the Geneva Seal requirements. The key is fine finishing, not a specific style, so as long as every surface of every component is treated with intent and craftsmanship, there is a good chance it will meet the finishing requirements for the seal.

Geneva Seal-certified Excalibur Automatic Skeleton Carbon by Roger Dubuis

Next up are shaped parts and supplies including screws, pins, strip or jumper springs, and actuating levers or cams. Any part that does not fall into the category of the balance and escapement, wheel train, jewels, or plates and bridges probably would fall into this category.

A chronograph would have a large number of parts covered by this category, which also means a variety of part styles that may not be able to be finished in the same ways. For this reason the category has one general clause and the rest are specific to certain parts. These components must have:

Inside this category a specific component is also focused on: the strip and jumper spring. These components require a bit of different thought when it comes to finishing.

Geneva Seal-certified Chopard L.U.C Perpetual Chrono

This inclusion may seem a bit odd since they today’s synthetically produced bearing jewels are mostly sourced from one or two main suppliers. However, bearing jewels play a large role in the precision of the movement and they are not necessarily of equal levels of quality. For that reason the Foundation Council saw fit to include them in the specifications. The requirements are as follows:

The Geneva Seal is visible at 3 o’clock on the movement of this beautifully finished Chopard L.U.C. Perpetual Chrono

The wheels in the going train and elsewhere in the movement are some of the most critical components for function, so finishing them to a high standard is somewhat dicey lest the tiny teeth become deformed or the wheel warps from the forces of polishing and filing.

There are the most requirements for wheels specifically compared to any other component in the movement, which is fitting since they make up a majority of the functional components. The requirements are split between wheels specifically in the going train (timekeeping gear train) and other wheels. Wheels in the going train must be:

Moving on to wheels elsewhere in the movement the requirements go down, but only because it tends to require similar finishing as to that of the gear train. Wheels that are not in the going train must be:

The Geneva Seal is visible at 2 o’clock on this Cartier movement

I want to stress that there are absolutely no requirements for the finishing of the balance or how it is to be constructed. The only requirements around the balance and escapement discuss aspects of the escapement lever, spring mounting, and escapement wheel surfaces.

It should be noted that this could result in some very non-traditional balance assemblies that only need follow the general guidelines for finishing throughout the rest of the movement.

This also completely allows the use of silicon hairsprings and silicon balance wheels, since there is no mention of requirements regarding the use of other metals for the components. What is specified is very different. Requirements for the escapement are defined as:

Next, the requirements discuss the stud and adjustment index for the balance spring, specifically how it is to be constructed to avoid any adhesives or glues as those are not permitted. The requirements state the following:

This brings me to materials, which is only specified briefly in any of the documentation.

Mainly, no components made of plastic polymers are allowed, which would exclude any carbon fiber components as the resin that is usually used falls into the category of polymers. The technical commission of the Geneva Seal will periodically take a look at new materials in use for watchmaking and can, at any time, adapt new criteria according to the development of new materials in watchmaking.

This is currently where silicon is trapped. The material is explicitly non-traditional and due to its nature, it cannot be finished. It doesn’t really need to be finished to remove machining marks since the surface comes out nearly perfect and no machining marks are ever created.

The only reason I can guess this isn’t already an accepted material is that the demand to use it is still very low since there are only six companies that even have permission to use the Geneva Seal. But I bet it will soon be an approved material since it is made in a finished state, it bears no machining marks, and it improves the functionality of many parts.

The technical commission may even be discussing it right now.

The Geneva Seal can be seen discreetly stamped at the top of this Cartier movement

Since 2011, the newly overhauled requirements cover not just the movement but also the components used for casing the movement, and the function of the watch as a whole. The components that interface with the movement and case are carefully detailed and certain components even have specific requirements.

Overall the finishing is expected to be in line with the finishing applied to the movement with fine milling and turning without burs, trimmed chamfers, and all parts must be true to the original reference kit provided for that model.

The casing components that are described are clamps and braces, dog screws, screws for the extensions and levers of the push pieces, casing-up rings, pivoting levers, and extensions of the push pieces. Some of these are called out specifically for part-specific finishing requirements, but they mirror things that have been stipulated about movement components. They are as follows:

Each watch – and every component for that matter – is inspected by the brand, which must also keep detailed records that are given to Timelab for inclusion in the Geneva Seal archives.

This is to maintain a running record of every single component that has been included in a watch marked with the Geneva Seal as well as the performance data of each cased-up watch. This is crucial for any dispute at a later date and to show proof of inspection rigor.

The tests performed on the cased-up watches simulate wear and track the actual performance against the stated figures regarding water resistance, timing accuracy, power reserve, and the individual functions of the watch.

To test water resistance (and to verify the maker’s claim), the watch is tested in either air or water to a minimum of 3 bars. If the watch is specified to have a higher resistance, that figure is tested.

The watch is tested to a negative pressure of 0.5 bars to simulate air travel. A watch does not need to be water-resistant to earn the Geneva Seal, but if it is not water-resistant that fact must be stated on the certificate.

To test the functions, the brand must outline and have approved a testing procedure that activates all the functions of the watch over one testing cycle. This allows the verification of any special functions and mechanisms that are not directly related to the telling of time.

The function test spills over into the accuracy testing as most of the functions are automatically activated over the seven-day accuracy testing period. This test occurs over seven consecutive days and sees the watch moved to simulate natural wearing on a person’s wrist. This specifically involves the watch moving through one revolution per minute for 14 hours before being stopped in a random position for 14 more hours.

All manual or automatic watches begin the test fully wound while the process is repeated for seven days. Automatic watches are never rewound (aside from the natural motion created by testing the movement), while manual winding watches are fully rewound every 24 hours.

Readings on day 0 and 7 are compared visually and against a reference time. The maximum amount of deviation allowed is less than or equal to one minute over the entire seven days.

Any automatically advancing functions are checked for accuracy at the end of the seven days, and if the watch features a perpetual calendar, the date is set to February 26 of a leap year at the beginning of the test to check the advancing of the date mechanism at its most complicated.

If the watch features a chronograph, it must be activated for the first 24 hours of the test.

Finally, for testing the power reserve, the watch is fully wound and left dial up to run down. The watch must meet or exceed its claimed power reserve.

If the watch features a chronograph, the power reserve must be specified to be considered when the chronograph is running or stopped. This is a big issue with chronograph watches as the accuracy and power reserve can drop dramatically from claimed values if the chronograph runs for a long time.

The contemporary movement architecture of this Louis Vuitton Flying Tourbillon is no impediment to it being Geneva Seal certified

After all of this testing, inspection, and terrific amounts of hard work, if the watch passes, it can be certified as having met the requirements and be marked with the Geneva Seal.

The physical seal stamp’s location must be approved and, if possible, be marked on the same part that carries the movement’s serial number. The brand is responsible for getting the movement (and perhaps case) marked at the Timelab office, which is in control of and responsible for maintaining the necessary equipment.

Previously the mark was engraved or stamped, but in 2014 a new development was introduced called “nanostructural marking” that allows the seal to be etched into the metal instead of the previous risky stamping and engraving that could damage components.

The new procedure developed with Geneva University (UNIGE) and MaNEP, a national center of competence in physics, will actually change how the Geneva Seal deals with counterfeiting as well. The seal could theoretically be added in hidden locations for each watch, specific to each serial number, so that only the people in charge of adding the seal will have a record of where it is.

The update allows for a dramatic increase in options for marking the movements since the laser-driven nanostructural marking barely changes the surface of the material with no force. This means that the mark can be applied in virtually any location without risking damage to delicate parts, simultaneously increasing design choices as it can also be done in three different sizes.

Geneva Seal certified Louis Vuitton Flying Tourbillon

While that was an exhaustive trip through the requirements for the Poinçon de Genève, I want to briefly impress upon you the importance of such a seal.

With any product of high quality, the best way to ensure that quality remains high is to have an external judge of merit from an organization that only becomes stronger when it does its job as strictly as possible.

When Patek Philippe dropped the Geneva Seal and created its own in-house certification, it unknowingly devalued the meaning of its own freshly minted quality seal. Not because the brand created watches with any less quality or perfection (Patek Philippe still is considered among the best watch brands ever), but because it no longer had impartial qualification of its products.

I don’t know anyone who would say the Patek Philippe Seal is not one of the gold standards, but since it is done in-house, there can always be the question of how rigorously the brand enforces it.

Having a seal that is based outside of a benefiting brand seems to me to be a better starting point.

The Geneva Seal is the oldest remaining qualification for high-end watchmaking, and since it has updated for a more meaningful certification, the watches bearing the seal can stand ever taller knowing they passed an extremely strict test of quality in every possible way.

The list of brands currently with Geneva Seal watches in their collection is a small one, with only the sixth brand having been added in 2016. The champion behind the seal, Vacheron Constantin, leads the small group comprising Cartier, Roger Dubuis, Chopard, Ateliers deMonaco, and now Louis Vuitton (with one watch).

The group might be small, but every piece produced with the Geneva Seal is equally outstanding. After reviewing all of the requirements, it should be clear that the effort that goes into a watch bearing the seal cannot be understated or dismissed.

The updated rules and the commitment to quality and tradition (while allowing for the future to mold the present) makes the Geneva Seal not just an indication of exceptional craftsmanship, but a legacy that stretches back through three centuries of watchmaking history.

And that is something worth mentioning every now and then.

For more information, please visit http://www.timelab.ch/en/123/provenance.

Thank you Joshua for your very clear, extensive and, I think, necessary explanation about the oldest and probably best certification ever! I particularly agree with one of your conclusions: “With any product of high quality, the best way to ensure that quality remains high is to have an external judge of merit from an organization that only becomes stronger when it does its job as strictly as possible.”

looks like an informative article! thanks for sharing this 🙂

[…] one of the most important things to know in this list, the Seal of Geneva[1], is given to watches that have reached the high standards set by Genevan artistry. Consider the […]

[…] or platinum Movement: automatic Caliber 2460 G4, 40-hour power reserve, 28,800 vph/4 Hz frequency, Geneva Seal Dial: 18-karat gold, hand-engraved, high-fire enamel, hand-engraved platinum or gold dog Functions: […]

[…] called the “Self-Winding,” which is powered by a Richemont group ValFleurier movement without Geneva Seal that is based on the Cartier 1904 MC from 2012 and was used in 2016’s Piaget Polo […]

[…] applied gold markers and gold dauphine hands Movement: automatic Caliber 12-600 AT stamped with the Geneva Seal Functions: hours, minutes, subsidiary seconds Auction price: CHF 100,000 at Christie’s Geneva, […]

[…] 9452 MC is also the first Cartier movement awarded the Geneva Seal. This hallmark was made possible by a new Cartier workshop within the Roger Dubuis factory […]

[…] In 2009, Cartier paid special tribute to its emblematic model: for the first time, a Tank was equipped with Caliber 9452 MC, the brand’s manufacture movement with a flying tourbillon bearing the prestigious Geneva Seal. […]

[…] have a keen eye for craftsmanship and quality. They would be familiar with the requirements of the Geneva Seal, yet at the same time insist that the straps of their new watches be made of the same leather as […]

[…] And, of course, it is stamped with the Geneva Seal. […]

[…] story ended there, it would already be worthy of praise, but the L.U.C Full Strike also bears the Geneva Seal, requiring every single surface of every single part was purposefully finished and/or decorated to […]

[…] plates that cover the movement or go even further with techniques that rival the criteria of the Geneva Seal and component mechanisms that speak of true […]

[…] 374, powered by manually wound, Geneva Seal-stamped Patek Philippe Caliber R TO 27 PS QR with official C.O.S.C. chronometer certification, was […]

[…] Taking a full nine years to complete, Caliber 89’s movement conforms to the strict specifications of the Seal of Geneva (see Point Of Reference: The Standards Of The Geneva Seal). […]

MDf Edge Bander Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *